Our industry is entertaining enough; that’s why we’re called Entertainment. But, we are human, and we do make mistakes. Those mistakes are at the heart of the Wall Street Journal’s latest article on the death of Sarah Guillot-Guyard at Cirque du Soleil’s KÃ back in June 2013.

When something so tragic happens, wouldn’t you think that the death and subject matter enough would merit a story without really having to do much to it? It’s disappointing to see Alexandra Berzon’s article in the Wall Street Journal on Sarah Guillot-Guyard’s death be so sensationalized. One would think that an article in such a publication would preclude that kind of pulp. Right? Am I dreaming past the “If it bleeds, it leads” kind of reporting?

It’s not really her fault, I guess. What people like to read about is other people bleeding.

I like what Alexandra Berzon normally says, I mean she is a constant writer on the plight of oil workers in our country, her WSJ work on that alone is pretty tremendous. But why treat oil workers like human beings suffering the plight of working so hard in an industry that treats those workers like shit, and write a story about KÃ that makes our people and our work seem like the perfect setting for an episode of The First 48? That’s rough, dude! If anything, you’ve just made it harder for us who research and write within our industry by betraying the trust of the people you were interviewing, because you sure apparently did betray the trust of those who let you in, and completely let you in. That part seems pretty painfully clear, from company member Erica Linz on Facebook. I’ve quoted here here en toto:

There is a written companion to the WSJ KÃ video… The first sentences are everything, EVERYTHING that was wrong with the media response after the accident. I won’t post it outright because those first words dump painful salt in a wound that a lot of us carry. (My friend Diane has posted a free link in the comments. If you are like me, you’ll read it even if it’s upsetting, and I don’t want you buying a subscription to Wall Street Journal to do so.)

Shame, shame on you Alexandra Berzon. You assured me and we spoke at length before I agreed to do your interview about how you were not going to treat Sasoun’s story as an “if it bleeds it leads” headline. You decried the actions of journalists who had and assured me that you were asking to speak to those who loved her so you could portray her as a real person and stitch together the sincere truth. Your first line eradicates any illusion of integrity you aimed to portray in those conversations. Blood and gore will always get attention… You may as well have put naked chicks and flashing lights around the article for hype if you were going to approach it with the level of class you did. I’ve seen porn ads more subtle. Even your choice of including the word basement in that first paragraph… an image that connotes childhood fears, darkness, isolation and the work of serial killers. Very clever… Surely the fatal accident wasn’t tragic enough to get people to read on it’s own.

I am appalled by you.

Let me say — I don’t have a Pulitzer like Alexandra Berzon. I mean, come on – my website is called JimOnLight.com for feck’s sake — really creative naming, I know. But seriously, read this – what’s the tone set here? It’s like reading some Tarantino:

Sarah Guillot-Guyard lay dying on the floor of a basement inside a darkened Cirque du Soleil theater here, one leg broken and blood pooling under her head.

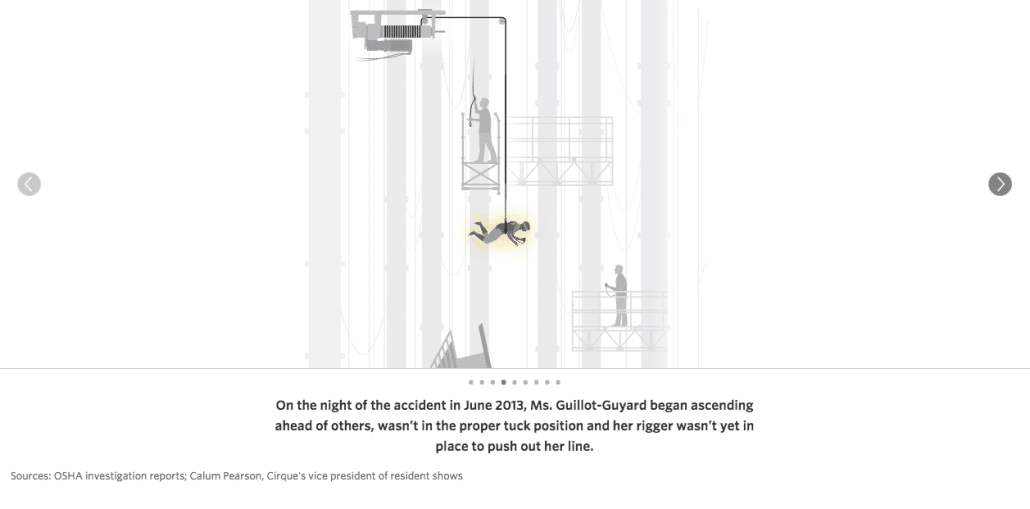

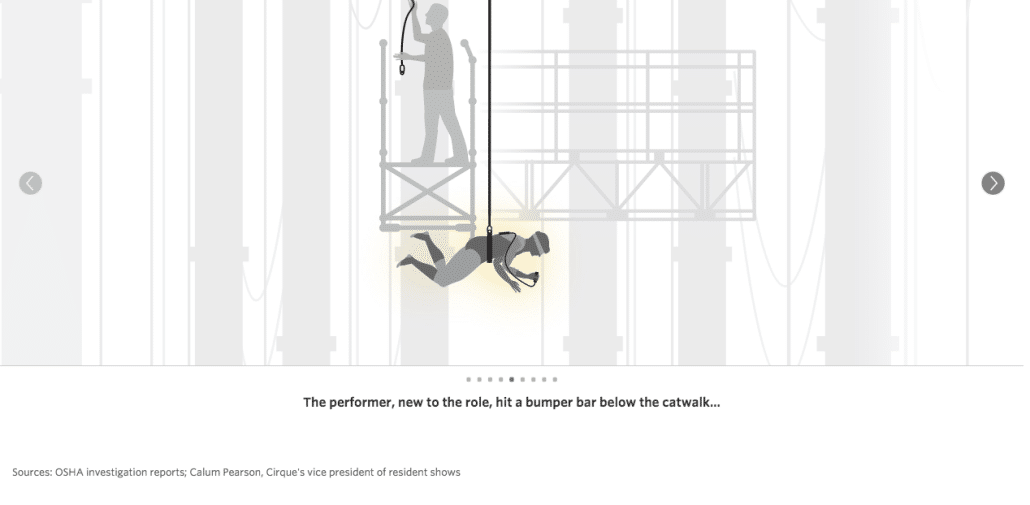

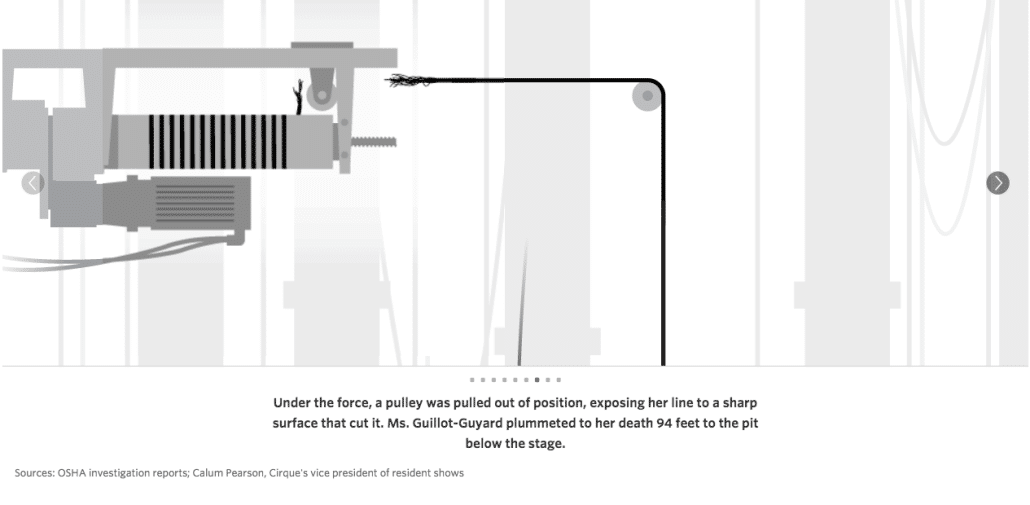

It was June 2013, and the 31-year-old mother of two had fallen 94 feet in front of hundreds of horrified spectators after the wire attached to her safety harness shredded while she performed in the dramatic aerial climax of the company’s most technically challenging production, “KÃ .”

It was the first fatality during a Cirque show, and it capped an increase in injuries at Cirque with the “KÃ ” production. The show had one of the highest rates of serious injuries of any workplace in the country, according to safety records kept by Cirque that were compared with federal records by The Wall Street Journal.”

Here’s a bit of a video on their story:

There are a couple of really odd things about the reporting on jobs numbers too, things that when you look at numbers and no backstory, it seems like it could potentially be feasible. Check out the chart posted in the WSJ story:

This graph is saying that per 100 workers, KÃ had an increasing injury rate, per 100 workers, of about 35 per 100 in 2010, 48-50 per 100 workers in 2011, and almost 60 per 100 workers in 2012. However, this is a odd selection of things to compare KÃ to, especially with respect to workplace injuries. Why not Stunt personnel, Commercial Divers, Military contractors?

Compared to Nursing and Residential Care facilities, Manufactured Home Manufacturing, Police Protection (a pretty broad category, frankly) Skiing facilities, for whatever reason, Construction, and Foundries, holy crap, KA has a SERIOUS increase in workers per 100. But the industries that the Wall Street Journal chose to select have tens of hundreds of thousands of workers!

Here’s the thing: As far as Ka goes, there’s about 80 employees. All techs and non-artistic management are MGM employees. Just to make this make a little more sense to anyone who is interested in making some sense out of these numbers, here’s the 2013 US Department of Labor’s Employer-Reported Incidents Report. It’s a PDF link, comb through it just a little and you will instantly see a problem with the way these KÃ stats were derived.

Also, for all of you nerds like me out there who like to see just behind the veil of journalism — although in this case, it’s more like a Fox News kind of play… here’s the raw data:

2012 US Department of Labor Employer-Reported Injuries Report

2011 US Department of Labor Employer-Reported Injuries Report

2010 US Department of Labor Employer-Reported Injuries Report

Please, comb through these and see if you find the same really odd comparisons here to industries with hundreds of thousands of workers.

OSHA Stats

Here’s some interesting data from the Occupational Safety and Health Organization that we all know as OSHA:

Worker injuries, illnesses and fatalities

4,585 workers were killed on the job in 2013 [BLS 2013 workplace fatality data] (3.3 per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers) — on average, 88 a week or more than 12 deaths every day. (This is the second lowest total since the fatal injury census was first conducted in 1992.)

817 Hispanic or Latino workers were killed from work-related injuries in 2013—on average, more than 15 deaths a week or two Latino workers killed every single day of the year, all year long.

Fatal work injuries involving contractors accounted for 16 percent of all fatal work injuries in 2013.

Construction’s “Fatal Four”

Out of 4,101* worker fatalities in private industry in calendar year 2013, 828 or 20.2% were in construction―that is, one in five worker deaths last year were in construction. The leading causes of worker deaths on construction sites were falls, followed by struck by object, electrocution, and caught-in/between. These “Fatal Four” were responsible for more than half (57.7%) the construction worker deaths in 2013*, BLS reports. Eliminating the Fatal Four would save 478 workers’ lives in America every year.

- Falls – 302 out of 828 total deaths in construction in CY 2013 (36.5%)

- Struck by Object – 84 (10.1%)

- Electrocutions – 71 (8.6%)

- Caught-in/between – 21 (2.5%)

Top 10 most frequently cited OSHA standards violated in FY2014

The following were the top 10 most frequently cited standards by Federal OSHA in fiscal year 2014 (October 1, 2013 through September 30, 2014):

- Fall protection, construction (29 CFR 1926.501) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

- Hazard communication standard, general industry (29 CFR 1910.1200) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

- Scaffolding, general requirements, construction (29 CFR 1926.451) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

- Respiratory protection, general industry (29 CFR 1910.134) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

- Powered industrial trucks, general industry (29 CFR 1910.178) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

- Control of hazardous energy (lockout/tagout), general industry (29 CFR 1910.147) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

- Ladders, construction (29 CFR 1926.1053) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

- Electrical, wiring methods, components and equipment, general industry (29 CFR 1910.305) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

- Machinery and Machine Guarding, general requirements (29 CFR 1910.212) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

- Electrical systems design, general requirements, general industry (29 CFR 1910.303) [related OSHA Safety and Health Topics page]

Frankly, there is a modicum of trust that people place in you when they invite you in to cover something so tragic as a fall death in the Entertainment Industry. Here’s how an industry writer does it; now Alexandra, I totally respect the way you do things in every instance except for this one, but here’s an opportunity to learn how to deal with this industry. This is from Jacob Coakley, one of the most prolific Entertainment industry writers to which I subscribe — this is from Jacob’s article Battle Tested:

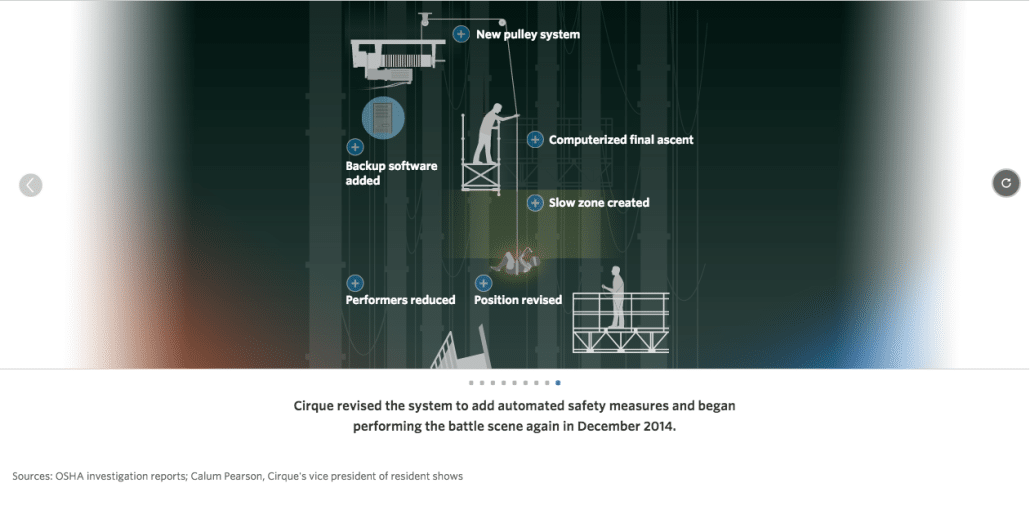

So what did Cirque do to insure an accident like this couldn’t happen again? The first and foremost factor in the accident was the speed at which Guillot-Guyard was ascending. Cirque has completely eliminated the possibility for performers to gain that speed. The final fly-out of artists off the top the platform is now fully automated, with limiters on the speed at which an artist can approach the grid. “This involves a zone large enough under the grid that no one can enter above a specific speed without being governed. If they do run to the zone at full speed, the software shuts them down.” And there’s a second software system monitoring the limiting software–if the first doesn’t shut down in an over-speed situation then the second one kicks in. “This can react quicker than a person on an emergency-stop switch, although we still have those in place, too, during the act,” adds Pearson.

They have also changed the behavior of winches when artists are still in front of the wall as well, though they haven’t automated that. “For us and the artists, it was important that they retained control of their winch lines throughout the majority of the act,” Pearson says. “This allows them to react with their bodies for the start and end of a move at high speeds. In doing so, it was still possible for collisions in the choreography to occur, so we engineered out the severity of those collisions by ensuring that if one person makes a mistake, the winch software and hardware will not allow them to continue until that error has been corrected. So ultimately it doesn’t remove human error, but makes sure that human error is not going to cause something worse to happen.”

They did this by changing how the winches operate under extreme load changes, replacing the primary and secondary brakes for new upgraded ones that won’t allow movement on the winch with the weight of two people on a line. The system also now uses no-load payout so if one of the lines sees zero weight on it, it will stop operating.

In terms of hardware, they lowered the winches to replace a small diverter wheel with a larger pulley block also bolted to the grid steel frames.

“We looked at every angle to see what could introduce an excessive shock load in the operating system and then worked with our engineers and manufacturers to remove the possibility of those forces being introduced during the act,” Pearson says. And to make sure the artists were comfortable with equipment, they brought in the manufacturers of each component in the system to explain how the system had been designed and how equipment choices were made to ensure safety. “We also brought the winches out of the grid, so we could show people up close what had happened and how we had mitigated it. This went all the way down to what bolts are used, what specifics are looked at in cable choices and how we maintain a 10:1 safety ratio. For some this was the first time they had touched the equipment at that component level, so we have identified that this will be an important part of new artist orientation in the future.”

Yet he admits that as a company that flies people, there will always be a level of risk. “We continue to focus on training and ensuring the most up to date upgrades on every piece of equipment. We take into account everything we can think of, such as power outages, to ensure that in those circumstances everyone knows how to respond and everyone in the air is safe. This is maintained through rigorous protocols such as rescue procedures, operational protocols and equipment enhancements, like artists wearing wireless communications so we can talk to them in the air as well as retaining a first response team on the show and holding monthly rescue trainings for any act that may require an artist to be helped down from a wire.”

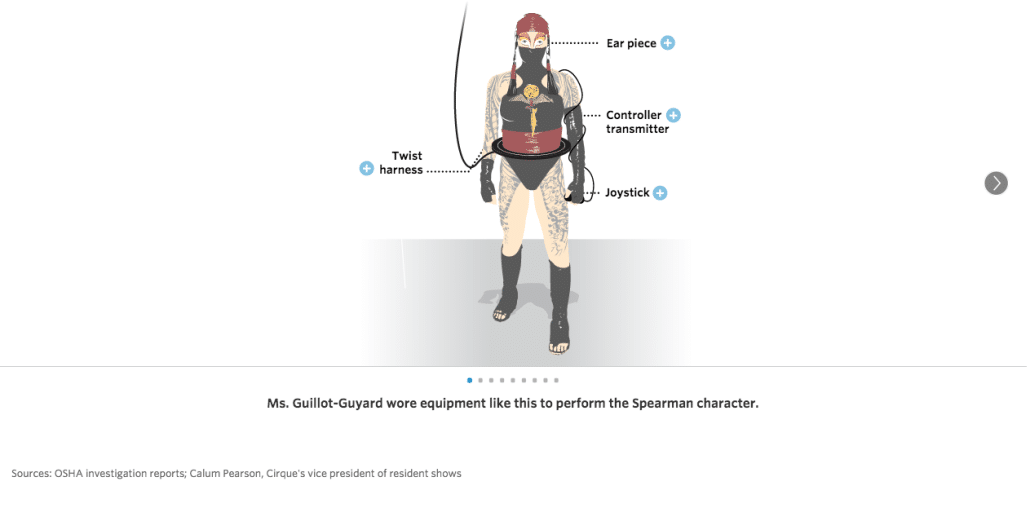

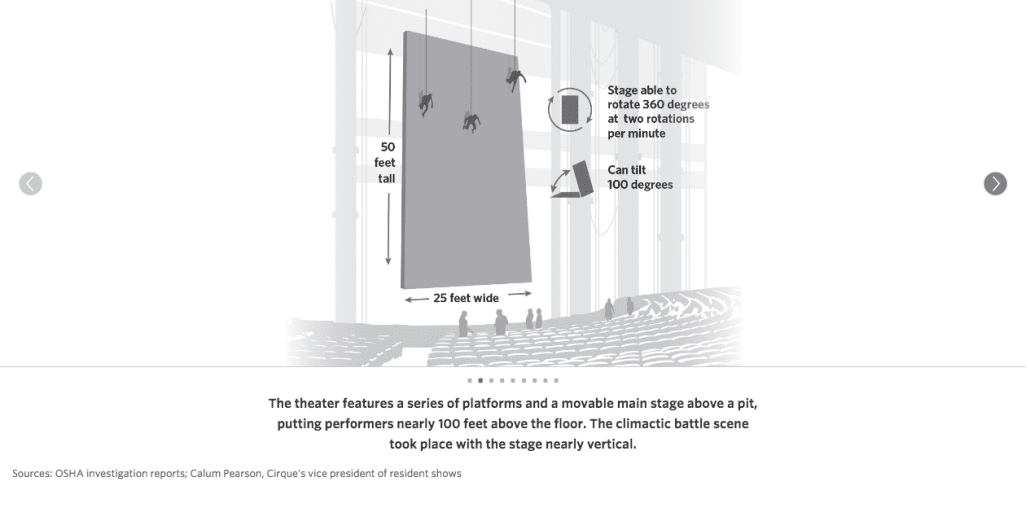

The Slideshow

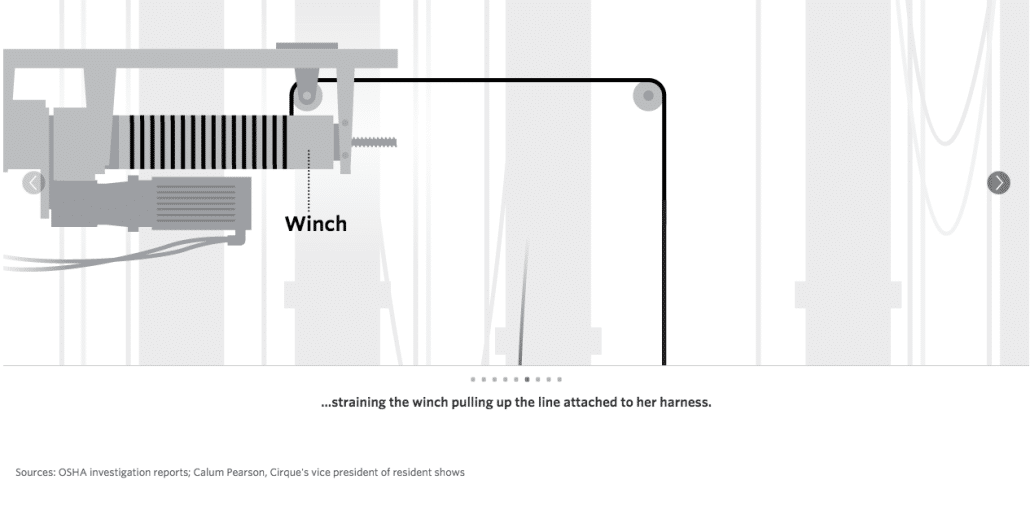

WSJ provided a bit of moving graphics along with the story to, you know, help the illiterate understand. I’ve taken the liberty of taking screenshots of the non-animation sections, hence screenshot… for those of you unfamiliar with the story, this part actually helps: